Introduction: The crisis of justice

Current crises seem to affect almost every aspect of human existence and all spheres of late modernity. Climate change, war, the rise of authoritarian illiberal democracies, the economic crisis, the long-term consequences of the coronavirus pandemic and Brexit are just some of the buzzwords that characterise this social development. The Émile Durkheim Research Unit: Crisis Analysis addresses this central question of the post-global era and focuses on the comparative-historical analysis of poly- and meta-crises. The aim is to analyse both the inherent logic/rationality of the individual crisis spheres and their interconnectedness - with the aim of making the knowledge generated available to other social actors and initiating dialogue with them.

The basic norm of justice is closely linked to crisis semantics. The omnipresent spread of the vocabulary of justice seems to be both an expression and a harbinger of the crises of the spheres. In large parts of our world, crises are increasingly perceived as resentment, resistance or anger about living conditions as issues of injustice, which are also to be understood as an expression of what Pierre Bourdieu called the ‘Misère du Monde’. This diagnosis of the times poses nothing less than the crucial question: How do we want to live together? And with it: Who are we? Where do we come from? And last but not least, where do we want to go? The debates thus touch on the profound structures and dynamics of late modern socialisation and bear witness to a ‘crisis of justice’.

Program, or: ‘How is a just society possible?’

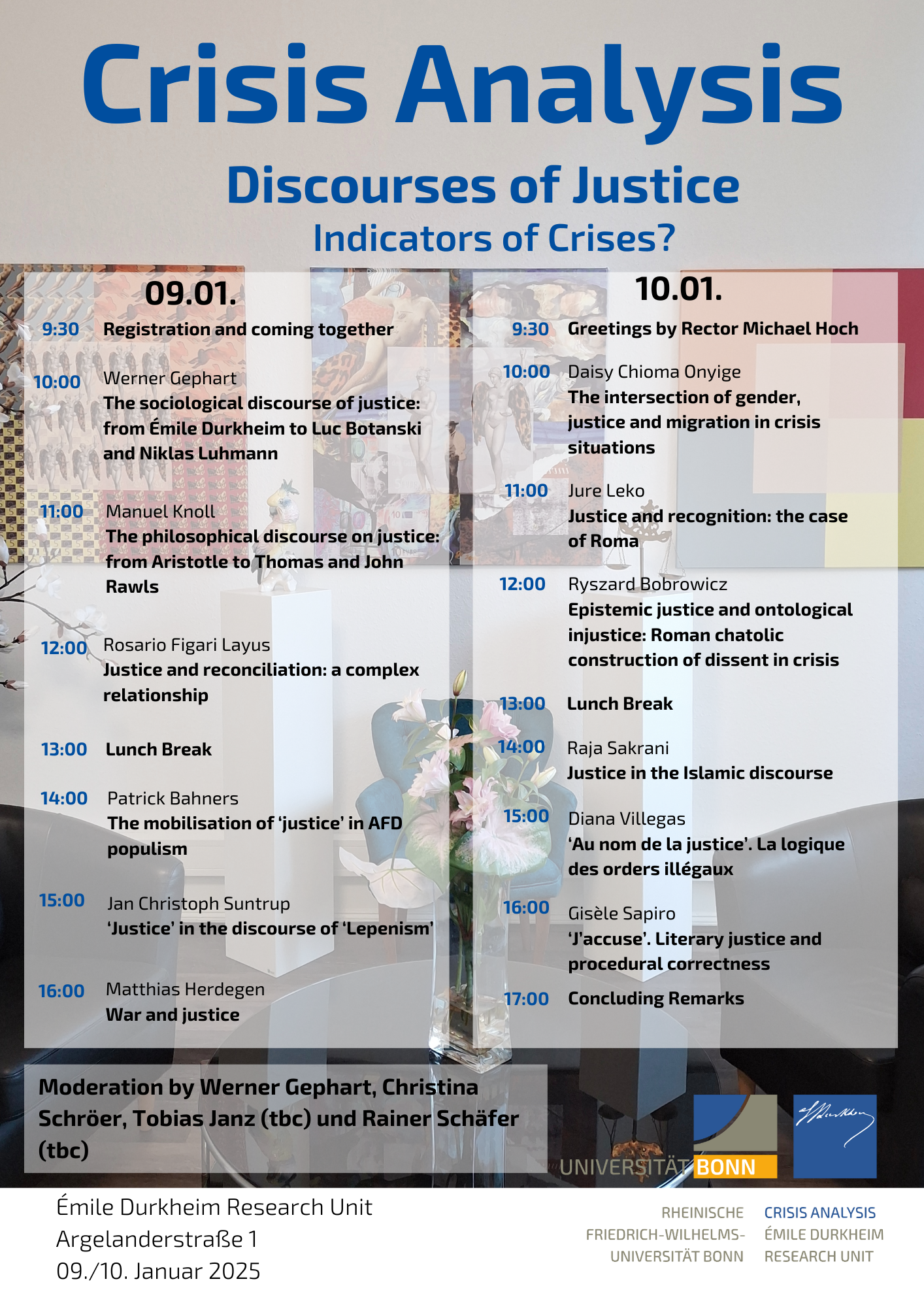

Against this backdrop, the Émile Durkheim Research Unit organised a symposium entitled ‘Discourses of Justice. Indicators of Crises?’, which was attended by renowned international guests from various disciplines..

In his welcoming address, the Rector of the University of Bonn, Michael Hoch, emphasised the current relevance of the topic of crises for society and research. Since he launched the Émile Durkheim Research Centre in 2024 as a further knowledge format of the Excellence university, global society has changed more than originally thought. The old world order is being restructured into a multipolar world order, new empires are emerging and are in open conflict with one another. These crisis scenarios are accompanied by a (perceived) increase in social inequality and social tensions. Against this backdrop, science seems to be operating in a safe space and it should be important to preserve academic freedom, to pass on the crisis knowledge generated to the scientific communities, including students, and transfer it to society.

Starting from the topic of the crisis, the Rector built a bridge to the conference topic of justice, which is particularly close to his heart as a developmental biologist. Both in his speech and in the ensuing discussion, he emphasised that, contrary to old assumptions, there is a sense of justice in parts of the animal world, which has been proven above all in some mammals. This in turn points to the evolution of feelings of justice, i.e. an emotive dimension, and is a plea for an intensification of the exchange between the natural sciences and the humanities - an interdisciplinary dialogue that the research centre promotes, particularly in connection with its annual topics, the climate and pandemic crisis.

Sociological and philosophical foundations

In his opening lecture, Werner Gephart, who heads the research centre, presented a sociological discourse on ‘justice’ and pointed out that, according to the sociological perspective, the social question of justice is inextricably linked to the question of social order. In view of the multi-paradigmatic nature of sociology, the answer varies. Based on Durkheim's study on the division of labour, he considers a comprehensive idea of justice that includes everything social and individual to be an obvious illusion; instead, he identifies various cités of justice in the sense of Luc Boltanski.

In order to analyse the ‘Cités of Justice’ in their complexity, he draws on the ‘Law as Culture’ paradigm and develops a concept that is specifically geared towards the analysis of ‘cultures of justice’. His proposal is to approach the observation of ‘cultures of justice’ (1.) multidimensionally and to include normative, symbolic, organisational and ritual aspects; (2.) to reveal the significance of religious reasons for validity; (3. ) to enable a globalisation-theoretical approach and to analyse universalist and particularist norms of justice in their interlocking; (4.) to take into account the dynamics of conflicts; (5.) to pay special attention to the role of aesthetics; and (6.) to incorporate the contingency of cultures of justice, which becomes particularly evident in times of crisis.

Manuel Knoll provides a philosophical basis for analysing cultures of justice. In his genealogy, he runs through various approaches to justice and illustrates these using selected crisis phenomena from the past and present. The spectrum ranges from egalitarian and social justice to meritocracy and procedural justice through to universal and particular justice. In contrast to Aristotle and Rawls, whose theories of distributive justice focus on a limited set of goods, Michael Walzer broadens the perspective with a more pluralistic approach. In the discussion, it emerges that Walzer's pluralistic approach is particularly suitable for understanding cultures of justice (in the sense of Werner Gephart) in their complexity and relating them to crisis contexts.

The struggle for justice in literature and law

While Werner Gephart and Manuel Knoll offer the sociological and philosophical foundations for analysing justice, the winner of the Humboldt Research Award, Gisèle Sapiro, focuses on analysing the literary field as a medium of justice. The birth of the intellectual emerged from the struggle for justice and triggered a process of social closure from which literature emerged as a relationally autonomous social field, according to Gisèle Sapiro's thesis. Using the examples of Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Zola and André Gide, she shows how intellectuals intervened in crises, communicated their ideas of law and justice to the public and thus contributed to the social validity and autonomisation process of the literary field. But what remains of the work when the authorship has placed itself politically and morally on the social sidelines? Can the literary work be separated from the authorship? In conclusion, she explores this question using the example of the controversial Nobel Prize winner Peter Handke and his fight for justice for Serbia, and shows ways of taking a differentiated approach to the discourse on work and authorship.

Rosario Figari Layus used the concept of reconciliation to show how crises of justice in transitional and post-conflict contexts can be dealt with socially. Using a genealogy of justice models of reconciliation, she demonstrates that reconciliation in the 1980s was primarily focussed on restorative justice (e.g. truth commissions, amnesties), in the 2000s on retributive justice (processes) and in the 2000s to 2010s on transformative justice (social justice). Since the 2020s, the idea of environmental justice (recognising and protecting nature) has emerged under this concept. Current challenges for reconciliation research exist above all in the connection between reconciliation processes and social inequalities. This requires more intensive research into intersectional perspectives that take into account the nexus of race, class and gender, and which are gaining both analytical and practical significance, particularly with regard to climate crises.

Can a war be just and what role international law plays in the definition of justice was the focus of Matthias Herdegen's presentation. He showed that collective traumas caused or triggered by war are difficult to translate into generally recognised legal relationships and thus make a successful reconciliation process more difficult The broad spectrum of subjective perceptions of ‘justice’ often leads to different interpretations, especially in complex international conflicts, according to Herdegen. One example of this is the parallel arrest warrants issued against the Israeli Prime Minister and the murdered leader of Hamas terrorism, which illustrate the contrasting views on justice and responsibility in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At the same time, he used several examples to illustrate the conflict between international jurisdiction and nation-statehood, with nation-state sovereignty representing a powerful barrier to the establishment of justice during and after the war. He emphasised that international law has come under severe pressure in the course of the reorganisation of world politics in recent years and is gradually losing its validity, which means that the possibility of a more just order of war is increasingly being lost.

The crisis of liberal democracy

The Franco-German reconciliation process shows how successful reconciliation can be after the war. At the same time, 60 years after the beginning of the process, a strengthening of the New Right can be observed in both countries, which appears to threaten the European post-war order, with the AfD and the Rassemblement National forming the party-political spearhead of this movement. Patrick Bahners and Jan Christoph Suntrup reported on the extent to which this current is plunging liberal democracy in Germany and France into a political crisis and the ideas of justice with which it is operating.

Bahners, one of Germany's leading feature writers, illustrated how the AfD has been driving a gradual shift in the democratic discourse on justice since its foundation in 2013, while at the same time attempting to undermine liberal democracy by democratic means. A central strategy of this counter-movement is to sharply criticise current migration policy. The ambiguity of the Basic Law is used in a targeted manner to prioritise the basic right to security for the ‘German people’ over the right to freedom of movement and settlement for migrants. This strategy is closely linked to the narrative that migrants represent a threat to the welfare state, as they allegedly live parasitically off the economic income of the native population - the nexus between migration and social welfare is precisely one reason for the success of the AFD, although similar strategies can also be observed in France.

The conflictual tension between particularist and universalist concepts of justice is also emphasised by Suntrup. In a historical overview, he worked out how a restructuring of justice narratives has taken place since Marine Le Pen took over the party. In order to achieve political success, the first question was how to win over voters from different political camps without losing the right-wing core support. To this end, it introduced the narrative of common sense as a principle of the centre and balance, as practised by the ‘normal’ population. The narrative is directed against the ‘predators from above’, the globalists, and the ‘predators from below’, the delinquents and criminals. The Rassemblement National constructs common sense as an alternative source of justice and ultimately positions it as an ideological critique of hegemonic liberal ideas of justice.

Daisy Chioma Onyige and Jure Leko use the example of migration to illustrate the serious, sometimes fatal consequences that particularist ideas of justice and nation-state identity politics can have. While Onyge analysed the vulnerability of women in the nexus of gender, justice and migration, Leko focused on the struggles for the recognition of Roma and the role of human rights. The lectures made it clear that even before the rise of authoritarian forces, the grand narrative of liberal democracy was in crisis. The thousands of deaths from African countries in the Mediterranean and the restrictive border policy towards Roma refugees from the Western Balkans are a harrowing testimony to the crisis of liberal moralism and its culture of justice. From a social theory perspective, it is not enough to speak of a migration crisis, as is often the case in politics and the media. Rather, the treatment of refugees points to the limits of international law and human rights and can therefore be understood as a crisis of modern statehood in post-global times.

From legal pluralism to the relationship between a culture of justice and religion

Diana Villegas used the concept of legal pluralism to shed light on the extent to which the emergence of irregular, state-unrecognised orders is an expression of a crisis of democratic nation-states. Using the example of mafia actors in Colombia, she illustrated how - in the name of justice - they pushed ahead with a reconfiguration of space and power by establishing a mafia-like order with its own legal system. Building on this, Villegas demonstrated how legalised and illegalised structures became increasingly intertwined, making it difficult in many cases to draw a clear line between legality and illegality. The legal ambiguity is by no means limited to Latin American countries; in the lecture as well as in the discussion, it emerged that this phenomenon can also be observed in numerous legal constellations in Europe and North America.

In his lecture, Ryszard Bobrowicz also focussed on non-state orders, their law and their social impact. Using the example of the Roman Catholic Church, he analysed the discourse on dissent in times of crisis and worked out the extent to which the concepts of ‘epistemic justice’ and ‘ontological injustice’ are effective in conflict resolution and what role the concept of synodality plays. Building on this, he analysed the social impact of religion in Europe and used several examples to show how religious norms shape political debates on secularity, are translated into state structures and thus maintain their respective functionality.

The relationship between the culture of justice and religion was also addressed by Raja Sakrani in her impressive lecture. Using the example of Islam, she showed what influence the diversity of schools of law, which can also be seen as ‘schools of justice’, has on social organisation processes and how these ideas of justice manifest themselves in aesthetics (architecture, art). She clarified the extent to which political Islam is characterised by an equation of religious obedience and the creation of just, inner-worldly conditions. In the context of the Arab Spring, this relationship was also broken up with reference to ‘alternative’ interpretations of religious dogma, so that a renewal of the promise of justice was initiated, the fulfilment of which, however, largely failed to materialise due to the failure of the revolution.

Resümee

Even if the topic of ‘justice’ may seem old-fashioned at first glance, the current social crises are evidence of its unbroken topicality. The diverse perspectives presented at the symposium emphasised this with clear vehemence. Especially in the current times of crisis, a new overarching ‘grand narrative’ or perhaps a renewed utopia of justice is needed in order to contribute to a more just social order. The lectures opened up a multifaceted view of the crisis of justice and encourage further exploration of the effectiveness of semantics in an interdisciplinary and international dialogue.