Welcome to the Homepage of the Émile Durkheim Research Unit: Crisis Analysis

The Émile Durkheim Research Unit focuses on the comparative-historical analysis of poly- and meta-crises of the 21st century.

It is based on the principles of internationality, interdisciplinarity, the Fellow principle and the formation of a thematically focused learning community on “crisis analyses” through Fellowships, which designate different disciplines and regions that are of particular importance in post-global times.

Call for Applications: Interdisciplinary Summer School

Crisis Analysis –

What We Can Learn from the Classical Theories of Durkheim and Bourdieu

The Émile Durkheim Research Unit invites applications for its upcoming interdisciplinary Summer School. This program aims to introduce students and early-career researchers to the scientific framework of crisis analysis, linking their personal experiences of crisis definition, perception, and resilience strategies to key theoretical perspectives.

Find out more here

Events

News

Research Unit

A thematically centered research center for the analysis of contemporary crises is being set up at the Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn as a further knowledge format of the university of excellence.

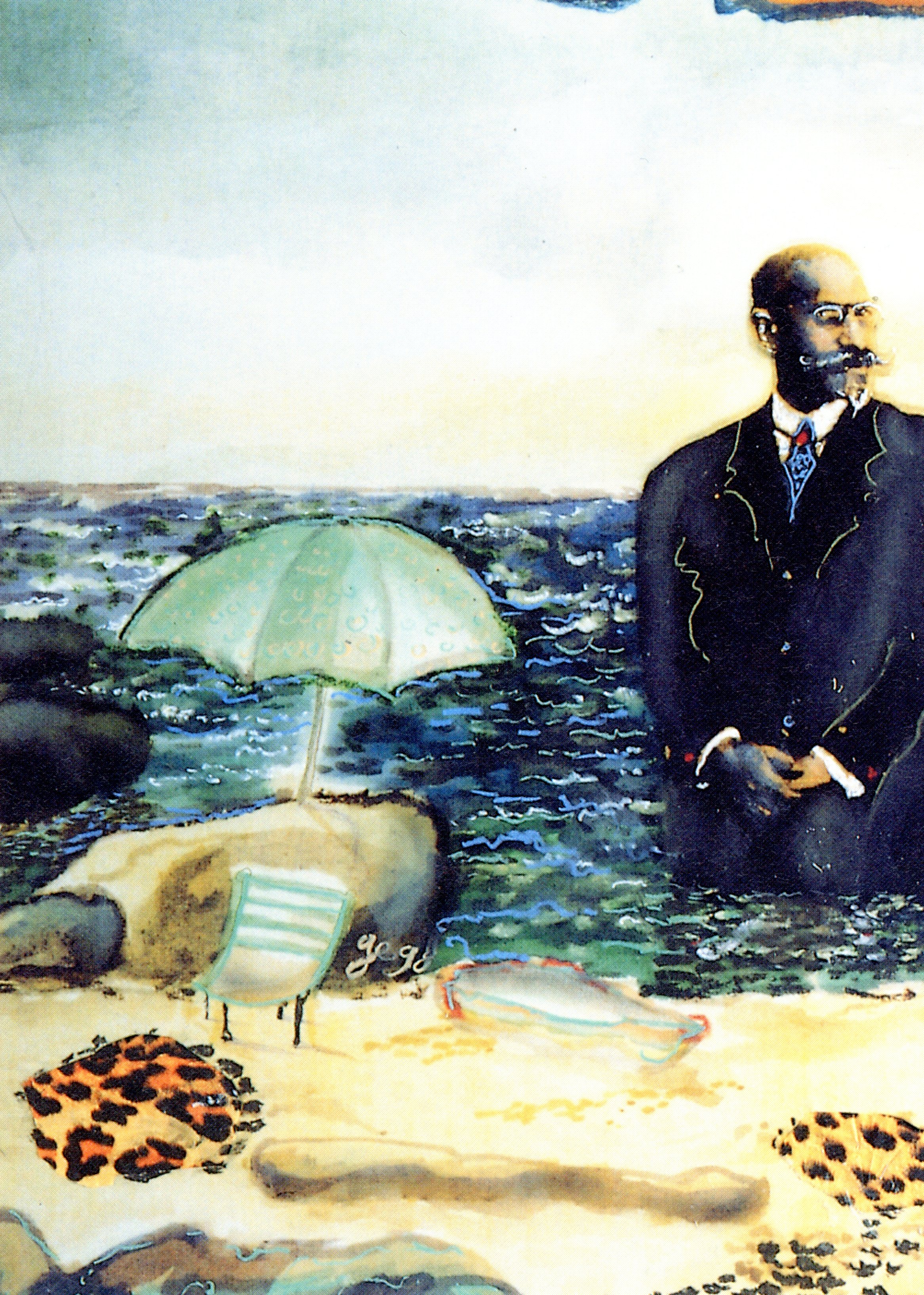

It is committed to the principles of internationality, interdisciplinarity and the fellow principle, which aims to find new questions and solutions in a learning community. With Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), it not only draws on a founding figure of the social sciences, but also opens the view to global reception from Marcel Mauss to Pierre Bourdieu and Bruno Latour, Mary Douglas to Cotterell, Talcott Parsons and J.C. Alexander, to name just a few. In view of Durkheim's delayed reception in Germany, it makes sense to honour the author, who was influenced by his study stays in Germany, which at the same time ostracized him under National Socialism. Despite a focus on the social sciences, Durkheim in particular offers numerous starting points for spanning the scientific cultures between the humanities and cultural studies as well as the natural sciences and for bringing them into a fruitful dialogue.

Subject of research

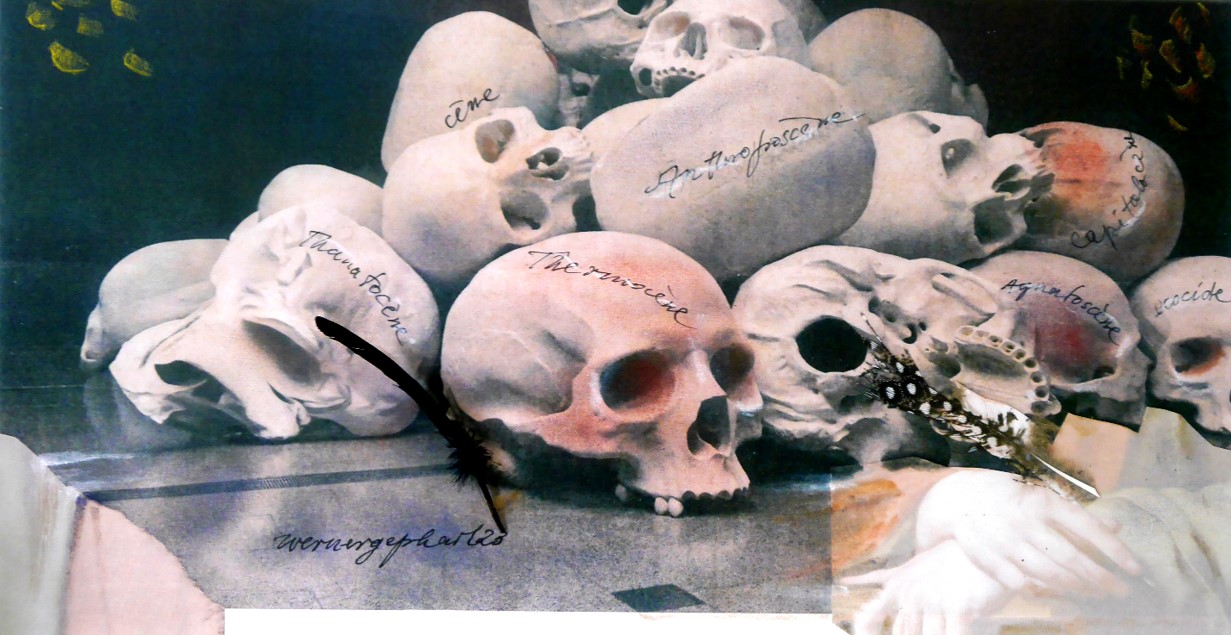

The research center would like to deal with challenges of the 21st century that manifest themselves in various crises, which were first analyzed in their breadth and interconnectedness by Durkheim. We encounter these developments as consequences of climate change, as a return of war, as a dramatic crisis of democracy, the inequality of the distribution of wealth and prosperity on a global scale or the crises of the “mind” in times of extensive digitalization and the advancement of artificial intelligence. We can expand this list to include financial crises, pandemic crises, crises of meaning and interpretation, etc., since almost every place in the “human condition” and all spheres of modernity (Max Weber) are susceptible to crises. They trigger discourses about justice and, taken as a whole, lead to a kind of “crisis of justice” that radiates into all areas of society. Discontent, resistance and anger about existing living conditions are expressed worldwide in a feeling of injustice that requires closer analysis. Depending on the media-influenced attention, these crisis phenomena are being researched in the respective disciplines of the natural sciences and humanities. However, the systematic-comparative analysis of the causes, consequences and interconnections of these crisis phenomena, as carried out in the individual disciplines, is neglected and deserves special research efforts.

Research objectives

Here, the concept of crisis, which Durkheim reserved in his study of the division of labor for the so-called “anomic”, i.e. insufficiently regulated division of labor, has an appeal character. As soon as a phenomenon is recognized as being in crisis and defined as such in public, a call is made to action. The question remains open as to what can be learned from crises that have already been overcome: the earthquake in Chili, the Spanish flu, from which Max Weber died in 1920 (!) or the horror of the world wars. This resulted in an unmistakable number of individual analyzes and suggestions for coping, which, of course, were not put to the test of comparative analysis. What about the perception and definition of what counts as a “crisis”, i.e. the “découpage de l’objet” as Durkheim calls it? Are there similarities in the dynamics of the crisis unfolding and the structural upheavals associated with it? Post-socialist societies have often been described as “anomic” transformations. Are there comparable coping strategies that are also transferable? And finally, crises are obviously intertwined to lead to accumulations and seemingly inextricable entanglements, which German constitutional law and its judges in Karlsruhe initially did not want to know about in the judgment of November 17, 2023, by the transfer of the funds that the federal government Originally provided in 2021 to combat the Corona crisis, may not be used for climate protection, i.e. the nature crisis. So would there be a need for a universal state of emergency or other constitutional options to take the interconnectedness of the crises into account?

And how could such interdependencies be interrupted? How do we deal with this seemingly inextricable intertwining of “polycrises” without losing the powers of systemic and personal resilience?

Research methods

Given such a complex problem, it is obvious that these questions cannot be analyzed and possibly answered by the individual researcher. And it is not enough to retreat to a single discipline; this only seems to be possible through the interaction of the scientific cultures of the natural sciences and the humanities. If the ecological crisis is already a global one, this also applies to crises in democracy or questions of meaning-making. It is all the more necessary to move away from a Eurocentric perspective in order to fundamentally exchange ideas with the perspectives of other cultures in the world, from problem definition and the formation of analytical categories to their solution approaches. In their sociological study of knowledge “De quelques formes primitives de classification” (1906), Émile Durkheim and his nephew Marcel Mauss showed that supposedly universal categories such as “time” and “space” are socially structurally and culturally determined. In times of profound post-colonial debates, which are already perceived as a crisis of “old European” thinking, we must open up to other cultures of thought down to our basic terminology, without arbitrarily giving up the Western reference. In this project, it will be important to bring together the forces of the Bonn University of Excellence with top-class scientists from all over the world. A link could be achieved by combining cross-sectional groups and research groups focused on annual crisis analysis topics. The task of one cross-sectional group will be to think about and reflect on the conditions of creativity, including visual imagination and analysis, as well as to bring together the results of the annual themes in the project of developing a historical-comparative crisis theory in a second group develop.

The Bonn University of Excellence offers an outstanding location for such a project, which not only arises from the competences of the University of Bonn, but is also based on the presence of numerous international organizations that are based in the federal city of Bonn.

Added value for the university and society

There is great agreement among many researchers around the world that the time for glass bead games and “intellectual gourmetness” is over. Émile Durkheim very impressively documented the value of intellectual work in his statements on the Dreyfus affair, from which the figure of the “intellectual” emerged in the first place. The sciences are called upon to face the special challenges of our time and to make their contribution. The President of the DFG, Katja Becker, opened the year 2023 with the article “Science and overcoming crises”. In our opinion, the task of the sciences is to face complexity and to search for innovative scientific solutions with all their might and to convey them. The Émile Durkheim Research Center at the University of Excellence Bonn offers an ideal place to take on this challenge.

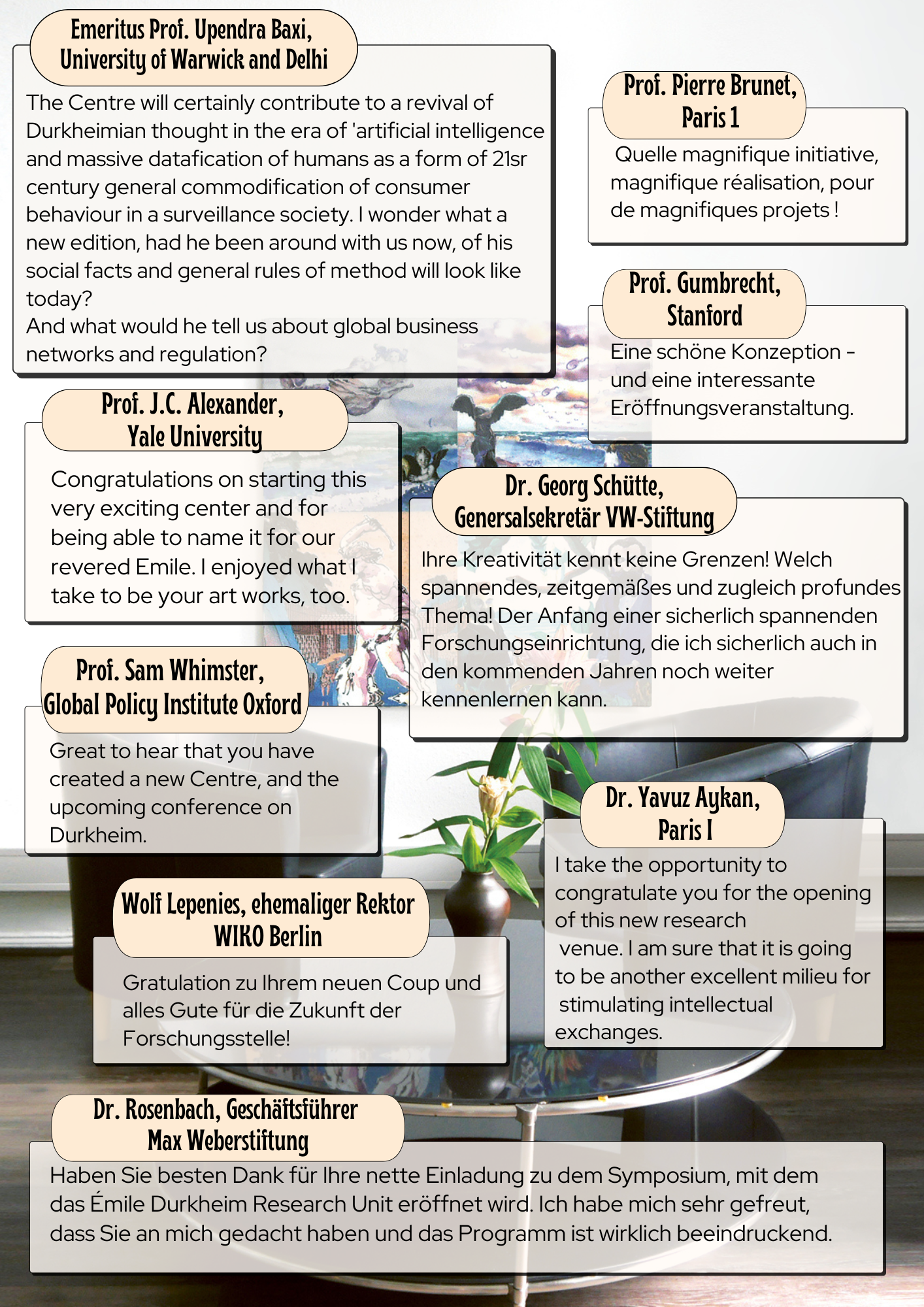

Reaktionen aus der Wissenschaft